An All-Encompassing Edifice of Life

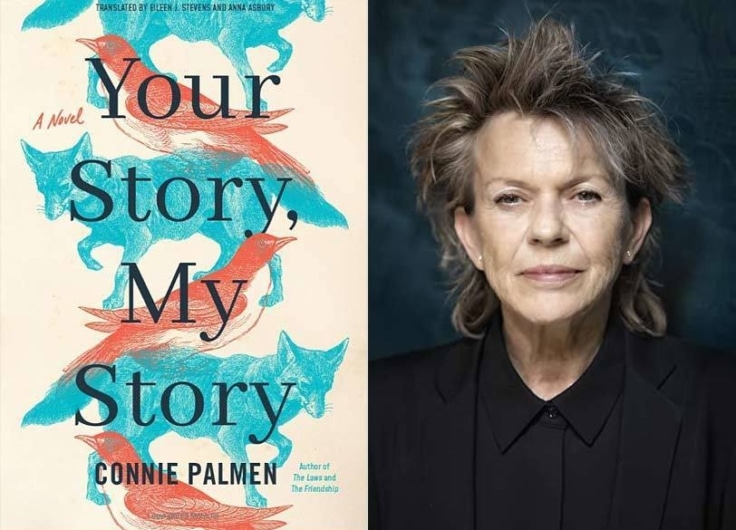

There is a popular theory that most authors keep on writing the same book, whereas only true writers build up their own oeuvre: an ingenious, cohesive edifice in which the core theme of each novel, story and essay – which of course constantly refer to one another – is illuminated from a different angle. If that holds true, it is especially so for the Dutch author Connie Palmen (b.1955), whose master’s dissertation, legend has it, contained the seed from which all her texts have grown.

Connie Palmen

Connie Palmen© Vera de Kok

The dissertation was titled Het weerzinwekkende lot van de oude filosoof Socrates (The repugnant fate of the ancient philosopher Socrates). Having graduated cum laude in Dutch studies, Palmen was awarded a master’s in philosophy for this work. The core of her argument is the theory that even someone like Socrates, who declined to write anything down for fear of being misunderstood, could not escape the fact that others would talk about him, form an image, project their ideas onto him – in short, give him a reputation. Socrates’ refusal to contradict that reputation, when accused of corrupting the Athenian youth, cost him his life.

People are defenceless against the stories which do the rounds about them, Palmen explains. But they are not responsible for those stories. Everyone has a public name, which gives them a certain reputation, be it in a small circle of acquaintances or in the broader social arena; however, it says nothing about who a person really is, but rather about the people who talk about them. “The Palmen you’re talking about, I can’t do anything about her,” she concludes.

This relationship between the false identity, symbolised by the name everyone knows, and the real identity, is a prevailing theme of her novels. Her work ranges from the dangerous attraction of fame to stalkers who believe television performances or novels address them directly, as discussed in Geheel de uwe (Sincerely yours, 2002), to research into the true story of perhaps the most talked about couple in literary history, the English-language poets Ted Hughes and Sylvia Plath.

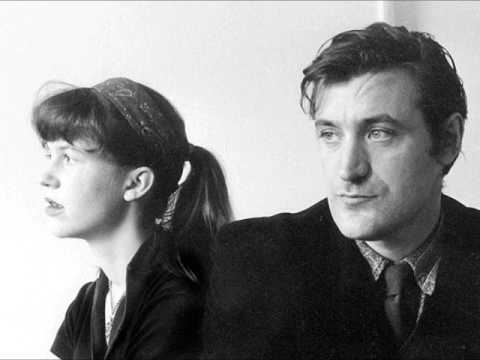

In the first paragraph of her latest novel Jij zegt het (You Said It, 2015), Hughes, to whom Palmen gives voice, begins, “For the past thirty-five years, I’ve had to watch with impotent horror as our real lives were buried beneath a mudslide of apocryphal stories, false witness, gossip, fabrications, and myths, how our true, complex personalities were replaced by hackneyed characters, reduced to mere images, tailor made to suit a readership with an appetite for sensationalism.”

Since her debut, De Wetten (The Laws, 1991), Palmen has been at the zenith of interest. There is a famous story that an article fell through at the daily newspaper NRC Handelsblad, the beacon of the intellectual elite in the Netherlands, and at the last minute the editors decided to place a glowing review of this debut work on the front page of their literary supplement. The article turned out to be irrepressibly enticing to the readership and in no time Palmen was the talk of the town.

Hans van Mierlo and Connie Palmen

Hans van Mierlo and Connie Palmen© Connie Palmen

Her status as a Dutch celebrity subsequently expanded due to her relationships, first with journalist and presenter Ischa Meijer, and a few years after his death with former politician Hans van Mierlo. Both men made her interesting to the media, which generally shows little interest in literature. Palmen further candidly engaged in self-exploration in her novels. Marie Deniet, the main character of De Wetten, and Catharina (alias Kit) Buts, the central character of De Vriendschap (The Friendship, 1995), are clearly recognisable as alter egos. Kit’s journey from an apathetic primary school child in Limburg to a bookish student in Amsterdam is Palmen’s own.

The highlight of this line in her oeuvre is I.M. (1998). Based on her own experiences with Meijer, with whom the spark ignites when he invites her onto his radio show, she describes the power of a searing love between a man and a woman who recognise from their first meeting that they are meant for one another, and of the ever-present pain to which this co-existence is doomed when it is interrupted – in this case by death. Many, if not all, readers, however, interpret the novel as an egodocument, not least because Palmen uses her own name and that of the journalist.

Palmen has nothing in common with the typical Dutch citizen, who prefers not to expose his head above ground level and, if he does, immediately puts his achievements into a wider perspective. Since her entrance into the public domain Palmen has exhibited pride in well-deserved fame. She writes rich, layered novels, in which every sentence contributes to the development of theme and plot. Why would she be modest about that? Has she not put the best of herself into it? Her work is simply better than the bulk of what is published.

Palmen’s entire work centres on that one theme of who a person is in the eyes of others

That proud, self-confident attitude shines through in her style. With stunning ease Palmen succeeds in employing big words for essential themes. Again we see that reflected in the opening pages of Jij zegt het, in particular in those short sentences which receive a separate paragraph: “It was real”, “It was her or me”, “I’d met my match in that all-consuming violence called love” and “Her death is my death.” But the amazing thing is, it works. The resolute tone is paired with profundity and intensity so that it only increases the reader’s belief in the story she serves up.

Against this background of oeuvre and personality it is easy to think that Palmen’s entire work centres on that one theme of who a person is in the eyes of others. Nevertheless it would be selling her novels and essays short to reduce them to that. Was De Wetten, in which the female protagonist embarks on a tour of seven men (referred to with titles such as ‘the astrologist’, ‘the priest’ and ‘the artist’) not also about the quest for love and her own place as a writer within the literary landscape?

Perhaps the fact that her work comprises all of life has become more visible since Palmen stopped taking her own life as the basis for her literary experiments. Lucifer (2007) is a roman à clef about the Dutch composer Peter Schat, whose wife died in suspicious circumstances on holiday in Greece in 1981. Jij zegt het is effectively a prose translation of The Birthday Letters, the cycle of poems in which shortly before his death Ted Hughes broke his thirty-five-year-long silence about Sylvia Plath’s suicide.

Sylvia Plath and Ted Hughes

Sylvia Plath and Ted HughesIn both cases the starting point is the stories doing the rounds. As the first-person narrator in Lucifer writes, they are the impetus that spurs her to search so exhaustively for the how and why of the tragic event (along with the fact that, put together, they fail to add up). But is the novel in the end purely about the inconceivability of the truth behind the stories? Not in the least. As the title – a reference to the play of the same name by the seventeenth-century iconic Dutch writer Joost van den Vondel – indicates, the story is primarily about arrogant rebellion against higher powers, reaching for the unattainable, the inevitable fall. The first-person narrator realises that there was more to the stories about Schat’s wife’s murder or suicide. Surely the message is that no novel succeeds with a single fact, a single idea?

The same goes for Jij zegt het. It is not first and foremost a vehicle for measuring the relationship between fiction and reality to the nth degree, but rather a study in the relationship between longing for love and longing for death. Can love be so strong that it removes the longing for death? Or does it in fact summon up the longing to disappear, so intensely that as the longing subsides one goes in search of other, more absolute forms of disappearance?

The feeling remains that both novels are sold short by reducing them to a suspected core. The work of a true writer – which Palmen unmistakeable is – cannot be reduced. A true writer’s oeuvre is an all-encompassing edifice, not a single theme, but life itself.

The following books by Connie Palmen have been published in English: The Laws (1992, Richard Huijing, Reed International Books and 1993, George Braziller), The Friendship

(2000, Ina Rilke, Harvill), Your Story, My Story (2021, Eileen J. Stevens, Anna Asbury, Amazon Crossing)